- Walmart Guns Shotguns Snake Charmer

- Snake Charmer Guns For Sale

- 410 Snake Charmer For Sale

- Game Show Moment Snake Charmer

- Snake Charmer 410 Shotgun

- Snake Charmer Game Show

- Snake Charmer Song

Mar 23, 2018 This of course includes the practice of snake charming; a type of traditional street performance commonly found in India. The snake charmer will appear to hypnotise the snake, getting it. Worlds collide and secrets are revealed as Natsu tries to face off with the mighty Ophiuchus!

| The Snake Charmer | |

|---|---|

| Artist | Jean-Léon Gérôme |

| Year | c. 1879 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 82.2 cm × 121 cm (32.4 in × 48 in) |

| Location | Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts |

The Snake Charmer is an oil-on-canvas Orientalist painting by French artist Jean-Léon Gérôme produced around 1879.[1] After it was used on the cover of Edward Said's book Orientalism in 1978, the work 'attained a level of notoriety matched by few Orientalist paintings,'[2] as it became a lightning-rod for criticism of Orientalism in general and Orientalist painting in particular. (Said himself did not mention the painting in his book.) It is in the collection of the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, which also owns another controversial Gérôme painting, The Slave Market.

Subject and setting[edit]

The painting depicts a naked boy standing on a small carpet in the center of a room with blue-tiled walls, facing away from the viewer, holding a python which coils around his waist and over his shoulder, while an older man sits to his right playing a fipple flute. The performance is watched by a motley group of armed men from a variety of Islamic tribes, with different clothes and weapons.

Sarah Lees' catalogue essay for the painting examines the setting as a conflation of Ottoman Turkey and Egypt, and also explains the young snake charmer's nudity, not as an erotic display, but 'to obviate charges of fraud' in his performance:

The Snake Charmer…brings together widely disparate, even incompatible, elements to create a scene that, as is the case with much of his oeuvre, the artist could not possibly have witnessed. Snake charming was not part of Ottoman culture, but it was practiced in ancient Egypt and continued to appear in that country during the nineteenth century. Maxime du Camp, for example, described witnessing a snake charmer in Cairo during his 1849–51 trip with Gustave Flaubert in terms that are comparable to Gérôme’s depiction, including mention of the young male disrobing in order to obviate charges of fraud. The artist has placed this performance, however, in a hybrid, fictional space that derives from identifiably Turkish, as well as Egyptian, sources.[3]

The blue tiles are inspired by İznik panels in the Altınyol (Golden Passage) and Baghdad Kiosk of Topkapi palace in Ottoman-era Constantinople. Some parts of the inscriptions on the walls cannot easily be read, but 'the large frieze at the top of the painting, running from right to left, is perfectly legible. It is the famous Koranic verse 256 from Surah II, al-Baqara, The Cow, written in thuluth script, and reads

There is no compulsion in religion—the right way is indeed clearly distinct from error. So whoever disbelieves in the devil and believes in Allah, he indeed lays hold on the firmest handle which shall never break. And Allah is Hearing, Knowing…

Walmart Guns Shotguns Snake Charmer

...the inscription thereafter is truncated…probably not a Koranic verse but rather a dedication to a caliph.'[4][5]

Regarding the snake depicted, 'Richard G. Zweifel, a herpetologist from the American Museum of Natural History…commented that 'the snake looks more like a South American boa constrictor than anything else,' a possibility that would add yet another layer of hybridity to the image. Gérôme could perhaps have studied such an animal at the Jardin des Plantes in Paris.[3]

Provenance and Exhibition[edit]

The painting was sold by Gérôme's dealer Goupil et Cie in 1880 to US collector Albert Spencer for 75,000 francs. Spencer sold it to Alfred Corning Clark in 1888 for $19,500, who in 1893 loaned it for exhibition at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. His wife and heir Elizabeth Scriven Clark loaned it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art before selling it to Schaus Art Galleries in 1899 for $10,000 or $12,000, in a transaction that might also have involved receipt of another artwork. It was acquired in 1902 by August Heckscher for an unknown price, then reacquired by Clark's son Robert Sterling Clark in 1942 for $500—a striking example of Gérôme's fall from favor with collectors. (Prices for his work have rebounded greatly in the 21st century, with paintings selling for millions of dollars.[6]) Since 1955 The Snake Charmer has been in the collection of the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, in Williamstown, Massachusetts.[1][7]

The Snake Charmer was included in the exhibition The Spectacular Art of Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904) at the Getty Museum in 2010 and the Musée d'Orsay in 2010-2011.[3]

Reception[edit]

In 1978, the painting was used as the front cover of Edward Said's book Orientalism. 'Since he defined his project as an examination of textual representations, Said never once mentioned Gérôme’s painting, but numerous subsequent authors have examined aspects of the artist’s work, and this painting in particular, in relationto the concept of Orientalism that Said defined.'[3]

Art critic Jonathan Jones bluntly calls The Snake Charmer

a sleazy imperialist vision of 'the east.' In front of glittering Islamic tiles that make the painting shimmer with blue and silver, a group of men sit on the ground watching a nude snake charmer, draped with a slithering phallic python.…The Snake Charmer is such an obviously pernicious and exploitative western fantasy of 'the Orient' that it makes Said's case for him. Gérôme is, you might say, orientalism's poster boy. In this influential work, Said analyses how Middle Eastern societies were described by European 'experts' in the 19th century in ways that delighted the western imagination while reducing the humanity of those whom that imagination fed on. In The Snake Charmer, voyeurism is titillated, and yet the blame for this is shifted on to the slumped audience in the painting. Meanwhile, the beautiful tiles behind them are seen as a survival of older and finer cultures which–according to Edward Said–western orientalists claimed to know and love better than the decadent locals did.[8]

Linda Nochlin in her influential 1983 essay 'The Imaginary Orient' points out that the seemingly photorealistic quality of the painting allows Gérôme to present an unrealistic scene as if it were a true representation of the east. Nochlin calls The Snake Charmer 'a visual document of nineteenth-century colonialist ideology' in which

the watchers huddled against the ferociously detailed tiled wall in the background of Gérôme's painting are resolutely alienated from us, as is the act they watch with such childish, trancelike concentration. Our gaze is meant to include both the spectacle and its spectators as objects of picturesque delectation.…Clearly, these black and brown folk are mystified—but then again, so are we. Indeed, the defining mood of the painting is mystery, and it is created by a specific pictorial device. We are permitted only a beguiling rear view of the boy holding the snake. A full frontal view, which would reveal unambiguously both his sex and the fullness of his dangerous performance, is denied us. And the insistent, sexually charged mystery at the center of this painting signifies a more general one: the mystery of the East itself, a standard topos of the Orientalist ideology.[9]

These critics insinuate that the snake charmer's nudity is a salacious invention on the part of Gérôme, unaware or dismissive of the explanation that disrobing was part of the act, 'in order to obviate charges of fraud.'[3] Salaciousness may lie in the eye of the beholder; although they cast their sentences in first-person plural or passive voices, it is Nochlin who perceives 'a beguiling rear view of the boy,' and Jones whose 'voyeurism is titillated'—though this would not qualify as his 'most shameful moment as a critic.'[10]

Ibn Warraq (the pen name of an anonymous author critical of Islam) in 2010 published a point-by-point refutation of Nochlin and a defense of Gérôme and Orientalist painting in general, 'Linda Nochlin and The Imaginary Orient.'[4]

References[edit]

- ^ ab'Clark Art—Snake Charmer'. www.clarkart.edu.

- ^Roberts, Mary. 'Gérôme in Istanbul' in Reconsidering Gérôme, edited by Scott Allan and Mary Morton, Getty Museum, 2010, pp. 119-134.

- ^ abcdeLees, Sarah. 'Nineteenth-century European Paintings at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute'(PDF). media.clarkart.edu. pp. 367–371.

- ^ abWarraq, Ibn (June 2010). 'Linda Nochlin and The Imaginary Orient'. www.newenglishreview.org.

- ^'Surah Al-Baqarah [2:256]'. quran.com. Retrieved 2019-10-17.

- ^'Jean-Léon Gérôme page at Sotheby's'. sothebys.com. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^Finkel, Jori (13 June 2010). 'Jean-Léon Gérôme's 'The Snake Charmer': A Twisted History'. latimes.com.

- ^Jones, Jonathan (3 July 2012). 'Jean-Léon Gérôme: orientalist fantasy among the impressionists'. www.theguardian.com.

- ^Nochlin, Linda. 'The Imaginary Orient', Art in America, (May 1983), pp. 118–131, pp. 187–191. Reprinted in The Politics Of Vision: Essays On Nineteenth-century Art And Society by Linda Nochlin, Avalon Publishing, 1989. Reprinted in The Nineteenth Century Visual Culture Reader, edited by Schwartz and Przyblyski, Routledge, 2004, p. 289-298.

- ^Jones, Jonathan (11 September 2015). 'I've read Pratchett now: it's more entertainment than art'. The Guardian. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

External links[edit]

- Jean-Léon Gérôme, The Snake Charmer, c. 1879 at YouTube, posted by Clark Art Institute

- Lees, Sarah. Nineteenth-century European Paintings at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, pp. 367-371.

- MacKenzie, John. Orientalism: History, Theory and the Arts, p. 46.

- Nochlin, Linda. 'The Imaginary Orient' in The Nineteenth Century Visual Culture Reader, edited by Schwartz and Przyblyski, p. 289.

- Roberts, Mary. 'Gérôme in Istanbul' in Reconsidering Gérôme, edited by Scott Allan and Mary Morton, Getty Museum, 2010, p. 119.

- Warraq, Ibn. 'Linda Nochlin and The Imaginary Orient', New English Review, June 2010

Media related to Le charmeur de serpents (Jean-Léon Gerome), 1879 at Wikimedia Commons

| Problems playing this file? See media help. |

'Arabian riff', also known as 'The Streets of Cairo', 'The Poor Little Country Maid', and 'the snake charmer song', is a well-known melody, published in various forms in the nineteenth century.[1] Alternate titles for children's songs using this melody include 'The Girls in France' and 'The Southern Part of France'.[2][3] This song is often associated with the hoochie coochie belly dance.

- 3In popular culture

- 3.1Music

History[edit]

The melody was described as an 'Arabian Song' in the La grande méthode complète de cornet à piston et de saxhorn par Arban, first published in the 1850s.[1]

Sol Bloom, a showman (and later a U.S. Congressman), published the song as the entertainment director of the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893. It included an attraction called 'A Street in Cairo' produced by Gaston Akoun, which featured snake charmers, camel rides and a scandalous dancer known as Little Egypt. Songwriter James Thornton penned the words and music to his own version of this melody, 'Streets Of Cairo or The Poor Little Country Maid'. Copyrighted in 1895, it was made popular by his wife Lizzie Cox, who used the stage name Bonnie Thornton.[2] The oldest known recording of the song is from 1895, performed by Dan Quinn (Berliner Discs 171-Z).[4]

The first five notes of the song are similar to the beginning of a French song named 'Colin Prend Sa Hotte' (1719), which in turn resembles note for note an Algerian or Arabic song titled 'Kradoutja'.[5]

The melody is often heard when something that is connected with Arabia, Persia (Iran), India, Egypt, deserts, belly dancing or snake charming is being shown.[citation needed]

The song was also recorded as 'They Don't Wear Pants in the Southern Part of France' by John Bartles, the version sometimes played by radio host Dr. Demento.

Snake Charmer Guns For Sale

Travadja La Moukère[edit]

In France, there is a popular song which immigrants from Algeria brought back in the 1960s called 'Travadja La Moukère' (from trabaja la mujer, which means 'the woman works' in Spanish), which uses the same Hoochy Coochy tune.[clarification needed] Its original tune, said to have been based on an original Arab song, was created around 1850 and subsequently adopted by the Foreign Legion.[citation needed]

Partial lyrics:

Travadja La Moukère | Travaja La Moukère |

In popular culture[edit]

Music[edit]

Since the piece is not copyrighted, it has been used as a basis for several songs, especially in the early 20th century:

- 'Hoolah! Hoolah!'

- 'Dance of the Midway'

- 'Coochi-Coochi Polka'

- 'Danse Du Ventre'

- 'In My Harem' by Irving Berlin

- 'Kutchy Kutchy'[2]

- 'Strut, Miss Lizzie' by Creamer and Layton

- In Italy, the melody is often sung with the words 'Te ne vai o no? Te ne vai sì o no?' ('Are you leaving or not? Are you leaving, yes or no?'). That short tune is used to invite an annoying person to move along, or at least to shut up.

- In 1934, during the Purim festivities in Tel Aviv, the song received Hebrew lyrics jokingly referring to the Book of Esther and its characters (Ahasaurus, Vashti, Haman and Esther) written by Natan Alterman, Israel's foremost lyricist of the time. It was performed by the 'Matateh' troup, under the name 'נעמוד בתור / Na'amod Bator' ('we will stand in line').

Later popular songs that include all or part of the melody include:[6][7]

1920s[edit]

- The 'Little Egypt' segment of the World's Columbian Exposition scene in Show Boat (1927)

1930s[edit]

- 'Twilight in Turkey' by the Raymond Scott Quintette (1937)

1940s[edit]

- This tune is quoted in Luther Billis' dance in 'Honey Bun' from the musical South Pacific. (1949)

- Bonaparte's Retreat' by Pee Wee King (1949)

1950s[edit]

- 'Istanbul not Constantinople' by Four Lads (1953) and They Might Be Giants (1990)

- 'Nellie the Elephant' by Ralph Butler (1956)

- 'Teenager's Mother (Are You Right?)' by Bill Haley & His Comets (1956)

- 'Ek Ladki Bheegi Bhaagi Si' from the motion picture Chalti Ka Naam Gaadi (1958)

- 'Oriental Rock' by Bill Haley & His Comets (1958)

1960s[edit]

- 'The Sheik of Araby' performed by the Beatles during their 1962 Decca audition, with George Harrison as the lead singer and Pete Best on the drums (this track can be found on Anthology 1).

- 'I've Got the Skill' by Jackie Ross (US #89, 1964)

- 'Revolution 9' by the Beatles (1968)

- 'Funky Mule' by Buddy Miles Express (1968)

1970s[edit]

- 'The Grand Wazoo' by Frank Zappa (1972)

- 'You Scared the Lovin' Outta Me' by Funkadelic (1976)

- 'Open Sesame' by Kool & The Gang (1976)

- 'One for the Vine' by Genesis (1976)

- 'Egyptian Reggae' by Jonathan Richman and the Modern Lovers (1977)

- 'King Tut' by Steve Martin (1978)

- 'White Cigarettes' by P-Model (1979)

1980s[edit]

- 'Menergy' by Patrick Cowley (1981)

- 'Lies,' by Thompson Twins, immediately after the line, 'Cleopatra died for Egypt. What a waste of time!' (1982)

- 'Starchild' by Teena Marie (1984)

- 'Egypt, Egypt' by The Egyptian Lover (1984)

- 'Jail House Rap' by The Fat Boys (1984)

1990s[edit]

- 'Iesha' by Another Bad Creation (1990)

- 'Place in France' by L.A.P.D. (an early band for 3 of the original members of Korn) (1991)

- 'Gypsy Reggae' by Goran Bregović (1993)

- 'Cleopatra, Queen of Denial' by Pam Tillis (1993)

- 'Cleopatra's Cat' by the Spin Doctors (1994)

- 'It's On Now' by 57th Street Rogue Dog Villains (1995)

- 'Skatanic' by Reel Big Fish (1996)

- 'Criminal' by Fiona Apple (1997)

- 'Hokus Pokus' by Insane Clown Posse (1997)

- 'Rip Rock' by Canibus (1998)

- 'Circus' (马戏团) by David Tao (陶喆) (1999)

2000s[edit]

- 'Playboy' by Red Wanting Blue (2000)

- 'Learn Chinese' by MC Jin (欧阳靖) (2003)

- 'Over There' by Jonathan Coulton (2003) (lyrics)

- 'Act a Ass' by E-40 (2003)

- 'Lækker pt. 2 feat. L.O.C.' Nik & Jay (2004)

- 'Naggin' by Ying Yang Twins (2005)

- 'Rojo es el color' by Señor Trepador (2006)

- 'Toc Toc Toc' by Lee Hyori (이효리) (2007)

- 'Ular' by Anita Sarawak (2008)

- 'Till You Come to Me' by Spencer Day (2009)

- '¿Viva la Gloria?' by Green Day (2009)

- 'Mr.Ragga!!' by Shonanno Kaze (湘南乃風) (2009)

2010s[edit]

410 Snake Charmer For Sale

- 'Space Girl' by The Imagined Village (2010)

- 'Take It Off' by Kesha (2010)

- 'Who's That? Broooown!' by Das Racist (2010)

- 'Grunt Tube' by Blue Water White Death (2010)

- 'Lipstick' by Orange Caramel (2012)

- 'I'm Not In Your Mind' by King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard (2014)

- 'Gloryhole' by Steel Panther (2014)

- 'Hypnotic' by Zella Day (2015)

- 'Back On The Train' by Phish (7/22/2015, Bend OR)

- 'Music To Watch Boys To' by Lana Del Rey (2015)

- 'Genghis Khan' by Miike Snow (2015)

- 'We Appreciate Power' by Grimes (2018)

- 'Hide Out' (사라지는 꿈) by Sultan of the Disco (2018)

- 'I'm So Hot' by Momoland (2019)

Cartoons[edit]

- Felix the Cat: Arabiantics (1928)

- Mickey Mouse: The Karnival Kid (1929)

- Mickey Mouse: The Chain Gang (1930)

- Mickey Mouse: Pioneer Days (1930)

- Mickey Mouse: Mickey Steps Out (1931)

- Circus Capers (1930)

- Betty Boop: Boop-Oop-a-Doop (1932)

- Flip the Frog: Circus (1932)

- Goofy Goat Antics (1933)

- Mickey Mouse: The Band Concert (1935)

- Mickey Mouse: Clock Cleaners (1937)

- Donald Duck: Self Control (1938)

- Donald Duck: The Autograph Hound (1939)

- Goofy and Wilbur (1939)

- Goofy Groceries (1940)

- Bugs Bunny: What's Cookin' Doc? (1944)

- Private Snafu: Booby Traps (1944)

- Aladdin's Lamp (1947)

- Popeye 'Nurse to Meet Ya' (1955)

- Woody Woodpecker: Witch Crafty (1955)

- Woody Woodpecker: Roamin' Roman (1963)

- Vincent (1982)

- The Simpsons episode 'Homer's Night Out' (1990)

- JoJo's Circus - used as the melody of the 'Snake Dance' song (2003)

- The Simpsons episode 'Milhouse Doesn't Live Here Anymore' (2004)

- Bob's Burgers episode 'Uncle Teddy' (2014)

- Family Guy episode 'Switch the Flip' (2018)

- Disenchantment (season 2) opening credits (2019)

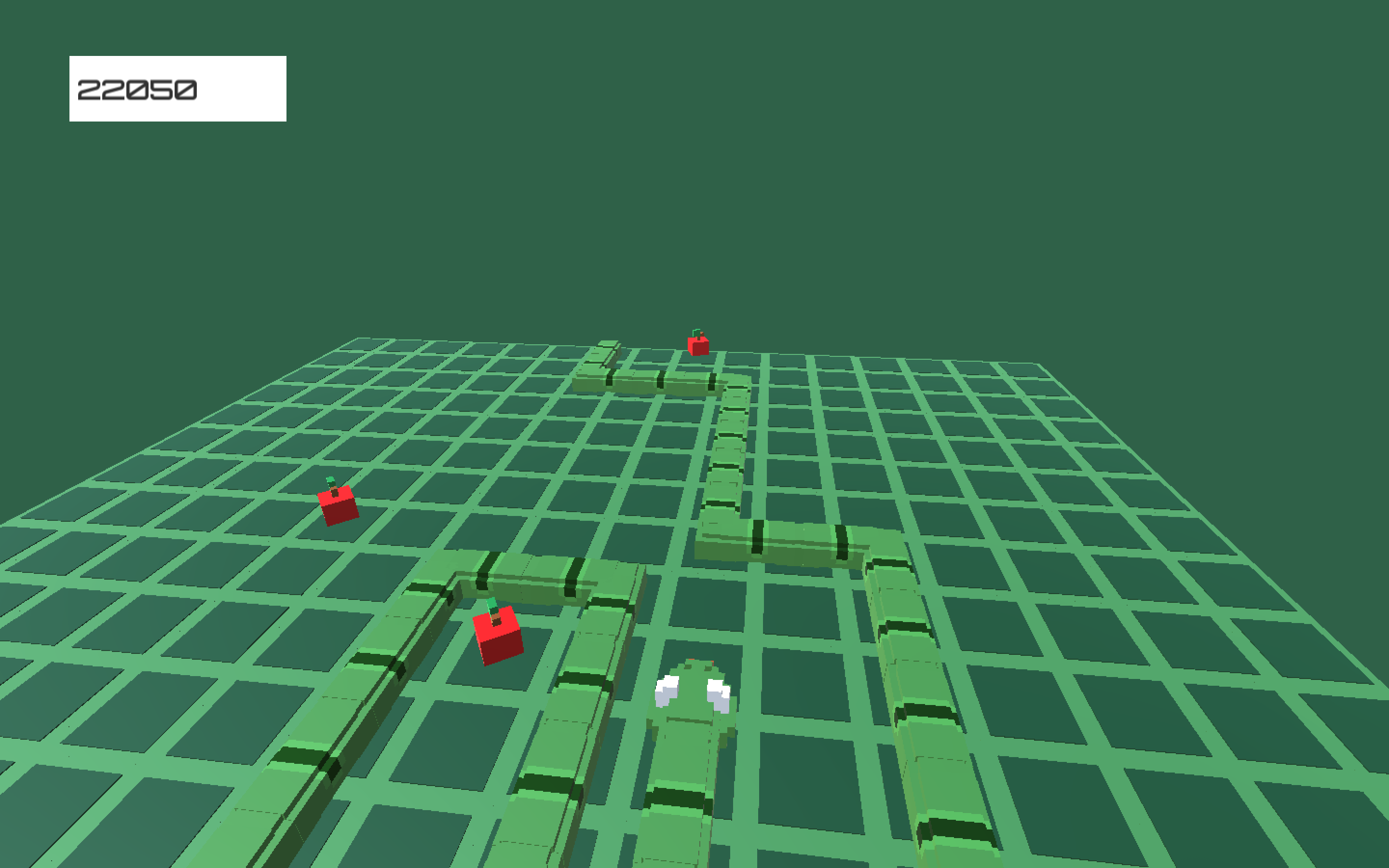

Computer games[edit]

From cartoons the song has been adapted to video games. It appears on following computer and video games:

- Dark Tower (1981 electronic game, bazaar)

- Venture (1981)

- Lady Tut (1983)

- Oh Mummy (1984)

- Bombo (1986)

- The Legend of Sinbad (1986, Level 2)

- Rick Dangerous (1989, Level 2 – Egypt)

- Quest for Glory II: Trial by Fire (1990, Katta's Tail Inn)

- Lotus Turbo Challenge 1 (1991, desert level)

- Jill of the Jungle (1992)

- The Lost Vikings (1992, Level 3 – Egypt)

- Lemmings 2 (1993, Egyptian tribe)

- Zool 2 (1994, Tooting common level 3)

- Rampage Through Time (2000, Egyptian timezone)

- Mevo and the Grooveriders (2009)

- Red Dead Redemption 2 (2018)

Television[edit]

- Andy Bernard sings a variation with a sitar in the 'Moroccan Christmas' episode of season 5 of The Office. Dwight Schrute also sings a variation about learning rules as a boy in the subsequent episode 'The Duel'.

Film[edit]

Game Show Moment Snake Charmer

- In Charles Lamont's 1932 short film War Babies, the first film in the Baby Burlesks series, the song is briefly used while Shirley Temple's character Charmaine is dancing around in Buttermilk Pete's Cafe.[citation needed]

- In Laurel and Hardy's Sons of the Desert (1933), it is heard briefly in a belly dancer scene at the beginning of the convention.

- It is heard in the beginning of Patrice Leconte's short film 'Le laboratoire de l'angoisse' (1971).

- In Emir Kusturica's 1993 movie Arizona Dream, the tune is being played several times with accordion by Grace.

Children's culture[edit]

The tune is used for a 20th-century American children's song with – like many unpublished songs of child folk culture – countless variations as the song is passed from child to child over considerable lengths of time and geography, the one constant being that the versions are almost always smutty. One variation, for example, is:

- There's a place in France

- Where the ladies wear no pants

- But the men don't care

- 'cause they don't wear underwear.[2][3]

or a similar version:

- There's a place in France

- Where the naked ladies dance

- There's a hole in the wall

- Where the boys can see it all

Another World War II-era variation is as follows:

- When your mind goes blank

- And you're dying for a wank

- And Hitler's playing snooker with your balls

- In the German nick

- They hang you by your dick

- And put dirty pictures on the walls

See also[edit]

- Oriental riff - similar musical motif, often associated with China

References[edit]

Snake Charmer 410 Shotgun

- ^ abcWilliam Benzon (2002). Beethoven's Anvil: Music in Mind and Culture. Oxford University Press. pp. 253–254. ISBN978-0-19-860557-7.

In compiling his collection of melodies Arban clearly wanted to present music from all the civilized nations he could think of. It is thus in the service of a truncated ethnic inclusiveness that he included an “Arabian Song”—or, more likely, the one-and-only “Arabian Song” he knew... Beyond this, the opening five notes of this song are identical to the first five notes of Colin Prend Sa Hotte, published in Paris in 1719. Writing in 1857, J. B. Wekerlin noted that the first phrase of that song is almost identical to Kradoutja, a now-forgotten Arabic or Algerian melody that had been popular in France since 1600. This song may thus have been in the European meme pool 250 years before Arban found it. It may even be a Middle Eastern song, or a mutation of one, that came to Europe via North Africa through Moorish Spain or was brought back from one of the Crusades.

- ^ abcdElliot, Julie Anne (2000-02-19). 'There's a Place in France: That 'Snake Charmer' Song'. All About Middle Eastern Dance. Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- ^ ab'France, Pants'. Desultor. Harvard Law School. January 21, 2004. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ^Settlemier, Tyrone (2009-07-07). 'Berliner Discs: Numerical Listing Discography'. Online 78rpm Discographical Project. Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- ^Adams, Cecil (2007-02-23). 'What is the origin of the song 'There's a place in France/Where the naked ladies dance?''. The Straight Dope. Creative Loafing Media, Inc. Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- ^http://www.whosampled.com/sampled/Sol%20Bloom/

- ^http://www.bilibili.com/video/av8860777/

External links[edit]

Snake Charmer Game Show

- 'Streets of Cairo' sheet music in the Levy Collection, via Jscholarship

- 'The Streets of Cairo or the Poor Little Country Maid' reference recording on YouTube

- 'The Streets of Cairo' Dan Quinn recording on YouTube